It’s been said at several places on this blog (and of course more fully elsewhere) that coral reefs are in big trouble, and that one of the best hopes for protecting them is to more fully recognise and realise the benefits (ecosystem and economic services) they offer to rapidly expanding humanity.

But there are other aspects to consider, including non-instrumental ones such as ethics (a right to existence, perhaps?) and aesthetics (sheer beauty).

[Despite the title, this post is not about the output of the

Department for Administrative Affairs, or similar bodies]

The challenge of finding a common language for right action with regard to marine ecosystems is huge, as it is in many other areas of human activity. It may or may not be surmountable. Whatever the outcome, steps in the right direction may include more exchanges and discussion about beauty.

As a starting point, priests and poets, geneticists and imams, sadhus and auditors, brigadiers, bus drivers and physicists will mostly agree that coral reefs and the life that goes with them are ‘pretty cool’. But that doesn't take us very far.

Pre-agricultural, indigenous and traditional cultures that may have had a non-instrumental relationship with ‘nature’ have largely been destroyed (assuming they ever really existed). Whatever legacy they may or may not hand on (I guess that languages such as

Pirahã have and had no word for abstracts like 'beauty', or need of them), it is unlikely ever to be enough in a world of

six and half going on nine billion people. We also need all that science and modern social and political networks, at their best, can bring to the party.

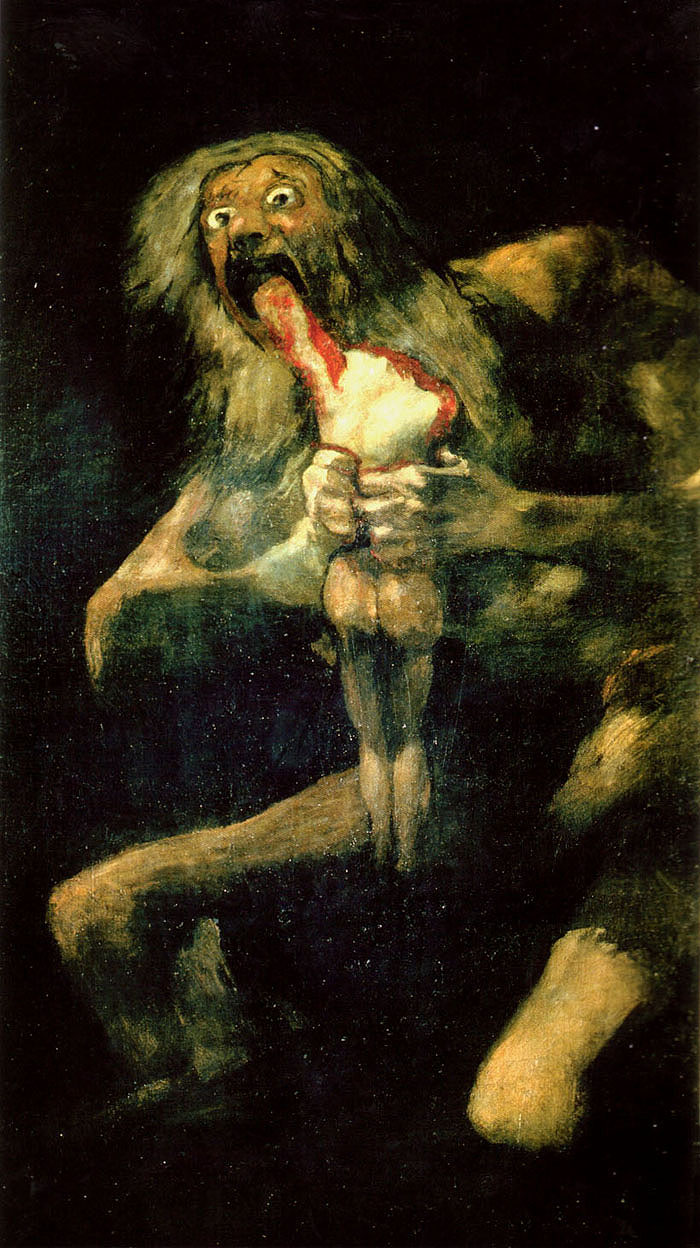

And a key question is value. Could aesthetic appreciation of what science reveals, informed and deepened by reflection, do for the natural world what Friedrich Schiller

hoped the arts would do for daily affairs: that they would ‘elevate the moral character of people by first touching their souls with beauty’? Could a 'sea ethic' be a corollary of Aldo Leopold’s

land ethic?

The political catastrophes of Schiller’s time and since show that enlightenment optimism should come with a pinch of salt. But that doesn't mean abandoning it. Projects like

The Encyclopedia of Life, inspired by E O Wilson and others, may help point the way.

There are many kinds of beauty on a reef. One is the sheer profusion of form and at the same time the echoing of some (but not all) forms and functions found elsewhere and at different scales in space and time. So (simplifying a bit too far) some corals look like trees and offer habitats in a similar way. Swimming over them can be like gliding over a great canopy in miniature. And two resonances – one from deep time and one from myth – may be examples. First, in the

Ediacarians of the pre-Cambrian:

[these were] made in a completely different way from other animals: they were fractal. Each frond was built up from smaller, identical fronds, and each of these was composed of yet smaller fronds, and so on, down to the smallest scale visible.

Second from a South Asian story as retold in

The Night Life of Trees:

The Peepul tree is the home of the Creator, worshipped by Hindus and forest people alike. They come from afar to pour water on the trunk in prayer. The Peepul tree is so perfect that even against the sky it seems to have the same shape as its own leaf. The detail is the same as the whole.

The links made with these two examples may be stretched. The point is to find connections and common language open to both imagination and reason so that, collectively and singly, we can pay more attention.

The snail in this picture climbed the fence outside the study window while I was writing. We humans will need to be more long-sighted than this humble mollusc, and we have less time.

[P.S. 11 May As noted on

Grains of Sand, Paul Klemperer asks some

useful questions, including 'Is it morally correct to value our great-grandchildren one-tenth as much as ourselves?' and 'Is human welfare the only criterion anyway?']

'The god thou servest is thine own appetite.' -- The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.

'The god thou servest is thine own appetite.' -- The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.